It began with the baby, round of head and sublimely naked, crawling innocently across the walls of New York’s otherwise tense and grimy subway stations. Keith Haring first made a name for himself in the early 1980’s filling every blank poster-frame in the city’s sprawling underground system with hieroglyphs: barking dogs, laser zapping flying saucers, rubber-limbed dancers-and the radiant baby that best represented Haring’s energy and humanity. This summer, his art is reappraised in a long-awaited retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. But Haring’s living legacy is on the streets, where his work was always more at home than in the white-walled confines of the gallery.

“The reason that the ‘baby’ has become my logo or signature is that it is the purest and most positive experience of human existence,” wrote Haring in his journal in 1986. “Children are color-blind and still free of all the complications, greed and hatred that will slowly be instilled in them through life.” Recognizing that early exposure to artwork and unfettered creative expression can go a long way in opening up new modes of viewing the world, Haring was tireless in his work with children of all ages and backgrounds. Collaborating on murals with kids in America’s hardest-hit inner cities and giving drawing workshops at museums everywhere form Bordeaux to Tokyo, Haring encouraged a world view that rendered racial, cultural and sexual differences unimportant in the face of a commonly shared humanity. “Whatever else I am,” he mused in a 1987 journal entry, ” I’m sure I, at least, have been a good companion to a lot of children and maybe have touched their lives in a way that will be passed on through time, and taught them a kind of simple lesson of sharing and caring.”

Like so many 20th-century artists before him, Haring was inspired by the coloring-book scribbles, splotches and unself-conscious renderings of the child’s interior world-a world uncluttered by inhibition and suspicion, unashamed of its polymorphous perversity. (In addition to Haring’s ageless and genderless icons, he created a large number of libidinous drawings filled with dancing penises and bodies piled on top of each other in mass ecstasy. While Haring was sensitive to the fact that such material was not appropriate for a young audience and made sure not to display it in public spaces that would be accessed by children, the motivation for such work came from the same wellspring as his primary-colored figures. Both baby and penis are symbols of life and the inevitable continuity of life-even in the face of death.)

But haring was perhaps the first to initiate an ongoing conversation between the world of art and aesthetics and the interests of young people, which accounts for the more than 27 projects he participated in with them from 1984 to his death from AIDS in 1989. “When I do drawings with or for children,” he noted, “there is a level of sincerity that seems honest and pure.” While he enjoyed great commercial success during his short career, Haring recognized that sincerity was not exactly a strong suit of the contemporary art scene-a fact that only strengthened his commitment to making art accessible to the general public. New York’s art critics questioned the theoretical and aesthetic viability of Haring’s work, which bothered him. In the end, however, this was not his only measure of success. “There is nothing that makes me happier,” he admitted, “than making a child smile.”

Haring’s drawings hearken back to the age of four, and it was this very coloring book style that enabled him to so easily include children in the artistic process. Typically, Haring would create a spontaneous large-scale drawing on a piece of paper, a mural or a city wall. Using his thick black lines as a boundary, Haring’s guest artists would proceed to fill in the volume of his figures with their own drawings, paintings and writings-a method that gave voice to thousands of young people who otherwise might not have had the chance to express themselves.

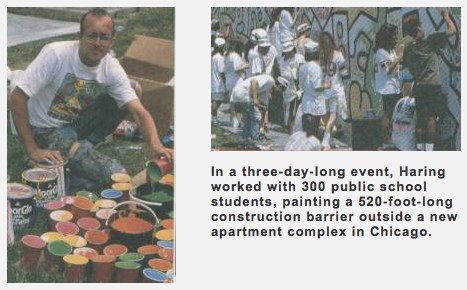

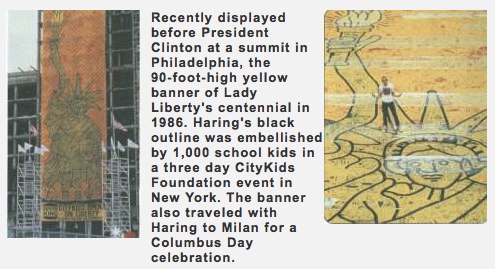

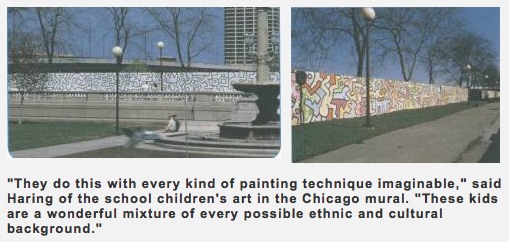

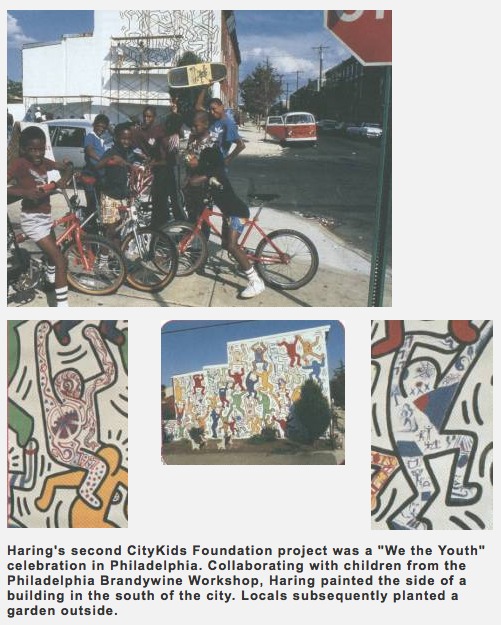

One of the most impressive of these projects was conceived in the summer of 1986 for the Statue of Liberty’s centennial celebration. In collaboration with the youth organization CityKids, Haring created a 10-story-high banner depicting Lady Liberty surrounded by a line of joyfully dancing figures. From afar, the banner-hung from a building in Battery Park City-was standard Haring. A close look, however, revealed the handiwork of 1,000 at-risk high school students who participated in a mass creative session sprawled out on the floor of the Jacob Javits Center. Similar events took place in Philadelphia and Chicago-occasions that had Haring marveling at the diversity of expression contained within the final result. “They do this with every kind of painting technique imaginable,” enthused Haring of the Chicago event-a 520-foot mural created with 300 public high school students. “All these kids are a wonderful mixture of every possible ethnic and cultural background.”

Haring’s sense of artistic authorship was a considerably looser than most fine artists of his time, who appropriated freely from the visual detritus of contemporary pop culture but would squawk at any sign of plagiarism or aesthetic “borrowing” from their own work. So synonymous was Haring’s cast of crawling, dancing and barking creatures with the 1980’s that he was faced with T-shirt and graffiti knock-offs everywhere he went. (In fact, he had a vast collection of such imitations.) In a partial effort to stem the tide of forgeries and to answer youth culture’s obvious desire for his work, Haring created the Pop Shop, a hole-in-the-wall SoHo store that sold affordable works of wearable art. More than an attempt to generate money by commercializing his artistic vision-Haring was already making top dollar from gallery shows-the Pop Shop was designed to further close the gap between art and the people.

The Pop Shop also enabled Haring to form one-on-one collaborative relationships with kids in the neighborhood. Sean Kalish, a 15-year-old actor and aspiring sculptor, remembers first meeting Haring eight years ago when he would stop into the small SoHo store on his way to auditions. It became quickly clear to the store manager that the seven-year-old Kalish had a penchant for artmaking and for the splashy, exuberant drawings that covered the Pop Shop’s walls and ceilings, so he took the boy to meet Haring. “After that, I’d visit his studio from time to time, “remembers Kalish, “and eventually we just started drawing together. He was pretty open with things like that.” Haring’s enthusiasm and Kalish’s burgeoning talent resulted in a series of collaborative etchings that are today part of the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. “He’d work on a plate for about five minutes and then he’d pass it to me,” explains Kalish of the technique-an ultimate merging of innocence and experience. “It kind of made my day.”

Haring’s wish to see his artwork in the public realm was realized time and time again, thanks to his indefatigable generosity and the imagination of collaborators around the world. And with the Keith Haring Foundation, the organization set up after Haring’s untimely death, the artist’s spirit continues in the form of funding commitments to such causes as the Boys Club of New York, Children’s Hope Foundation, Children’s Village and UNICEF. An unrealized project conceived for Japan’s Tama City, however, aspired to be one of the grandest-and most poetic-expressions of Haring’s creative vision. In this land art piece, all of Tama’s residents between the ages of 6 and 18 would hold mirrors that, when seen aerially by plane or satellite, would form an immense radiant baby. Haring was enthusiastic about the project’s extended concept, which was to have children around the world do the same thing, in Moscow, Paris, Tokyo, Shanghai, New Delhi, New York, Los Angeles. “My baby would actually crawl around the entire globe,” he mused. To see his work emblazoned on the earth’s surface from the vantage point of space would no doubt be a thrill, but artistic authorship was not the issue. The symbolism was. “Children,” he concluded, “are the bearers of life in its simplest and most joyous form.”

Andrea Codrington is a New York-based writer specializing in visual culture.

This article was published in Sphere Magazine, 1997.

The Haring Foundation has received permission from the writer to publish this essay on www.haring.com.