“The drawings I do have very little to do with classical, post-renaissance drawings, where you try to imitate life or make it appear to be life-like. My drawings don’t try to imitate life; they try to create life, to invent life. That’s a much more so-called primitive idea, which is the reason that my drawings look like they could be Aztec or Egyptian pr Aboriginal… and why they have so much in common with them. It has the same attitude towards drawing: inventing images. You’re sort of depicting life, but you’re not trying to make it life-like. I don’t use colors to try to look life-like, and I don’t use lines to try look life-like. It’s also much more Pop, I guess, after growing up in a really carbon-and comic-dominated period. And, also, growing up with Pop art.“1

As Haring’s personal assistant and studio manager during the last six years of his life, I observed, absorbed and learned from his passion for life and art, helped him to explore, formalize and refine business relationships, navigated the increasing demands on his time. I provided support and bore witness to his daily routines, social interactions, celebrity, struggles and successes, both creative and personal. Our backgrounds were different, but we shared many interests, our social circles intersected, we worked well together, and we established a deep, reciprocal trust. When he became ill and decided to create the Keith Haring Foundation, I was honored to accept his offer to be its executive director.

I have now held that position for 18 years, and my responsibility is to promote and manage a legacy: respecting past connections and relationships, cultivating and nurturing new ones, staying true to Haring’s artistic and philanthropic goals, and doing whatever is needed to ensure his place in history. I frequently consult, advise and collaborate with museums, galleries, publishers and art historians. I escort works on loan from our collection around the world and speak about Haring’s philosophies of life and art to audiences of all nationalities and ages, keeping his message alive, as I know he would have wished.

When we were approached by the Egon Schiele Centrum to present the work of Keith Haring in Cesky Krumlov, I was immediately enthusiastic. Not only does this exhibition afford us the opportunity to bring Haring’s work to the Czech Republic for the first time, but I was interested in some of the parallels between Schiele and Haring.

“…During his short but highly prolific career which ended with his premature death, he created more than three thousand works on paper and approximately three hundred paintings. Contemporary accounts of his personality, as well as his own letters, reveal a young man driven by an egotistical faith in the immortality of his talent, who nevertheless lamented his struggle for public recognition…Numerous self-portraits portray an uninhibited exhibitionist, but in reality he was said to be shy and sensitive. His preoccupation with sexuality and existential explorations of the human condition convey him both as a product of his time and an artist who achieved aesthetic maturation when he was barely post-adolescent…“2

The text quoted above could accurately describe either artist. Although their approach to making art and their subject matter were different, both Schiele and Haring were precocious, incredibly prolific, obsessive workers – producers of voluminous quantities of images, with both artists’ oeuvres consisting primarily of drawings. They each found their signature style at in their early 20s. They were both extraordinarily ambitious self-promoters, supremely confident in their own artistic abilities, but criticized for their arrogance and the audacity of the ideas and relationships explored in their work. They were both sexually compulsive and were both condemned for their depictions of explicit sexuality and its transformative energy. Tragically, both artists fell victim to their own generation’s most devastating epidemics (which claimed an estimated 40 million lives apiece): Schiele died in 1918 at age 28 of Spanish influenza, Haring in 1990 at 31 of AIDS.

Accessibility and democracy are hallmarks of Haring’s philosophy of art, and the editions on paper we have loaned to the Egon Schiele Centrum speak very directly to this philosophy. For Haring, printmaking was a fertile “middle-ground,” a natural bridge medium between his unique works and the reproduction of his imagery on affordable apparel, posters, buttons and other commercial products. Haring experimented with numerous printmaking techniques throughout his career, even as he was investigating diverse media in his unique work, and simultaneously seeking alternative channels for promoting and sustaining the accessibility of his increasingly popular imagery. Lithography, silk-screening, etching, woodcuts, embossing – Haring worked in all these “replication” techniques, partnering with publishers in the US, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, France, Denmark and Holland. Haring’s abiding love of collaboration also found an outlet in the print medium – he collaborated with William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, illustrating their texts in silk-screened editions and bound books, and later joined forces with a 7-year-old child, producing a charming portfolio of etchings.

As Haring matured, his subject matter deepened and became more complex, and as a gay man living with AIDS, the politics and fear surrounding the late-20th-century epidemic became a dominant theme in his work. But, he never abandoned his basic, iconic visual vocabulary. In 1990 (just one month before his death), he published his final edition on paper, a portfolio of 17 silk-screens (“The Blueprint Drawings”) which duplicates a group of his earliest and purest visual narratives, originally created in 1981 as a series of unique sumi ink on vellum drawings.

Haring was a product of his time, and within his art one finds frequent allusions to electronic media, computers, TV, cartoons and UFOs. But there is also imagery that refers back to tribal patterns and representations of beasts and monsters seen in the iconography of Aztec, Mayan, North African and Aboriginal cultures. With humorous, disquieting irony, Haring created an extremely personal iconography, a kind of bestiary reflective of the anxiety, euphoria, oppression and hope of life on city streets. He sought to celebrate life and dissolve boundaries between human and animal, sacred and profane, while also exploring racism and the socio-political issues and horrors that surround AIDS.

Most of Haring’s works are untitled. He preferred to leave interpretation to the viewer – his interest was in forging a link between the imagination of the artist and the audience. He was more intrigued by the visceral response than by the studied interpretation cultivated by historians. As Haring said, “The only way art lives is through the experience of the observer. The reality of art begins with the eyes of the beholder, through imagination, invention and confrontation.” Haring often put his technique and talent in service to the specific message – whether commenting on sex, racism, religion or disease, the gay artist encouraged dialogue and, often, controversy. Haring’s accessibility, politics, subject matter and recognizable style also attracted an audience of young people – and it was via his public, commercial and philanthropic efforts that he continued to expand his reach beyond the museum and gallery to reach the broadest possible audience.

Haring has been the subject of several international retrospectives. His work is in major private and public collections, including those of the Museum of Modern Art; the Whitney Museum of American Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Art Institute of Chicago; the Bass Museum in Miami; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Ludwig Museum, Cologne; and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

Before his death, Keith Haring established a foundation in his name to maintain and enhance his legacy of giving to children’s and AIDS organizations. Throughout his career, Haring produced murals, sculptures and paintings to benefit hospitals, underprivileged children’s groups and various community health organizations. The Foundation is also committed to sustaining and expanding public awareness of Keith Haring. By working with museums, galleries, publishers and art education programmers, the Foundation is able to provide information and artwork to the public that might otherwise remain unexplored in archives.

Julia Gruen

Executive Director

Keith Haring Foundation

January 29, 2007

New York, NY

Footnotes

- 1.C. Flyman. Interview with Keith Haring, September 26, 1980

- Mary Chan. Exhibition brochure text from “Egon Schiele: The Leopold Collection, Vienna,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, 1997.

This essay accompanied the exhibition:

Keith Haring Graphics

Egon Schiele Centrum

Cesky Krumlov, Czech Republic

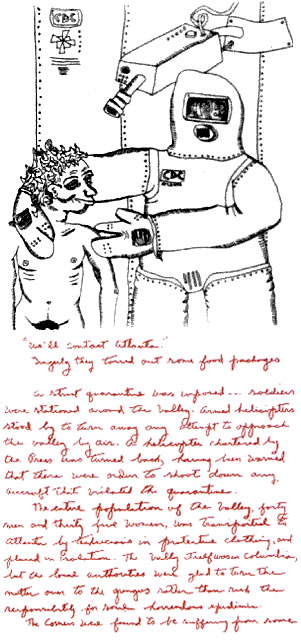

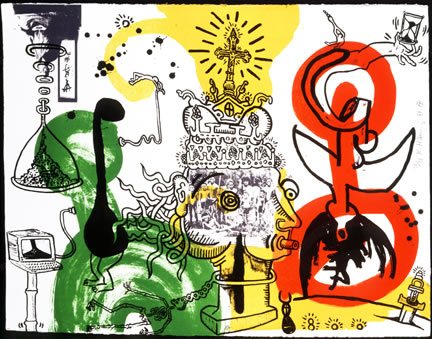

Apocalypse, 1988, Silkscreen | 38 x 38 inches | 96.5 x 96.5 cm

Text: Willliam S. Burroughs

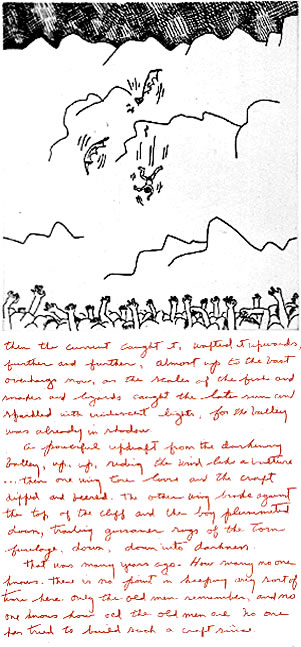

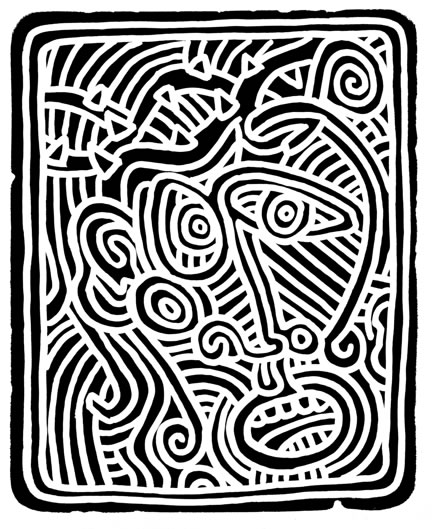

The Valley, 1989, Etching | 10 x 9 inches | 25.4 x 22.8 cm

Etching | 10 x 9 inches | 25.4 x 22.8 cm

Untitled, 1989, Etching | 12 7/8 x 11 1/2 inches | 32 x 29 cm

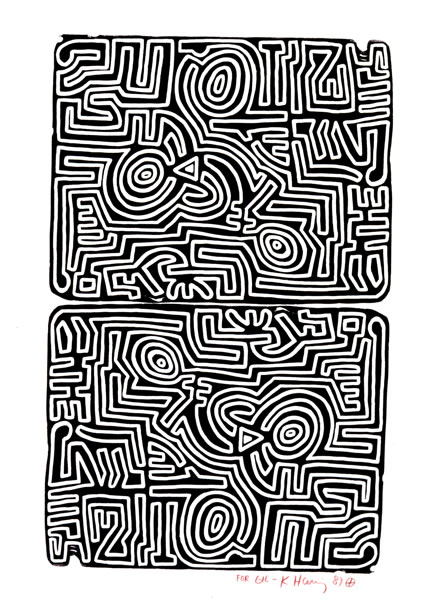

Labyrinth, 1989, Lithograph | 29 1/2 x 41 1/2 inches | 75 x 105.5 cm

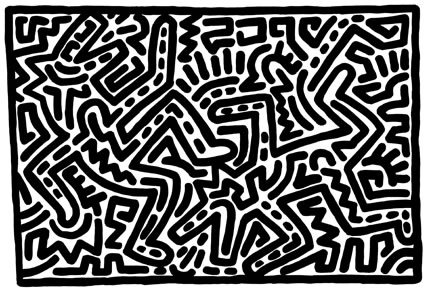

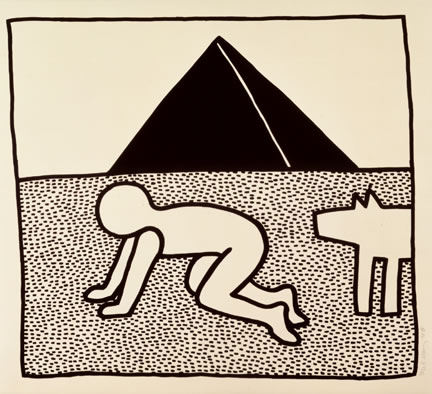

Untitled, 1982, Lithograph | 24 x 36 inches | 61 x 91 cm

Untitled, 1982, Lithograph | 24 x 36 inches | 61 x 91 cm

Lithograph | 23 x 29 3/4 inches | 58.5 x 75.5 cm

Chocolate Buddha, 1989, Lithograph | 30 x 27 3/4 inches | 56 x 70.5 cm

Stones, 1989, Lithograph, 30 x 22 1/4 inches | 76 x 56.5 cm

The Blueprint Drawings, 1990, Silkscreen | 42 1/2 x 46 1/2 inches | 108 x 118 cm