Gianni Mercurio You’ve been following Keith Haring’s work for twenty years. Has your opinion about him changed?

Jeffrey Deitch Not really. Although I do think it’s gratifying to look back from here and see that Keith has become part of the foundation of contemporary art today. Keith did more than make nice paintings and drawings and sculpture. He is one of those special artists who expand the definition of what an artist is, of what an artist can do – of what art is. This fast new art world that manifests itself in artists’ products, artworks in the street, T-shirts, and posters is directly connected to Keith’s influence. He brought art back into the realm of young people, inventing a vocabulary they can use.

Keith made works that can hang in museums alongside masterpieces by Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol and hold their own as art-historically important pieces. But there’s also the art world you see on the streets, and Keith helped make that happen. He took what he learned from Warhol and connected it to street culture-punk-rock posters, graphics on sports equipment, kids’ clothing, the music scene, and the club scene-and created a counter art world. Today we’re seeing a revival of that world-artists like Barry McGee are coming back into the gallery after having begun on the streets.

G.M. You have discussed the transforming influence that Andy Warhol had on the art world. Where do you think Haring fits into this “Warholization” of art?

J.D. Keith’s work is very much based on his hand – on mark, on drawing – whereas Warhol’s is more mediated. Warhol took images from pop culture, then transmitted them with silkscreen. Because the hand is central to Keith’s process, his work comes right out of his body. So there’s something fundamentally different there. Of course, Keith learned so much from Warhol about repeating images and expanding the art image into new channels. Some of the response to his work raises the question of whether Keith succeeded too well in disseminating his images. He has been misunderstood by more conservative people in the art establishment who can’t see past the Haring images on kids’ T-shirts and knapsacks and acknowledge his drawings and paintings as works in the tradition of the modern masters. In the past few years, he has begun to be accepted and valued on a par with other major contemporary artists. But there’s still a gap. You don’t walk in and see a Keith Haring hanging prominently in most American museums. I think that the art establishment has a hard time reconciling someone who is a great painter or sculptor and also really embraces popular culture.

G.M. Why do you think Haring’s work was more readily accepted by European than American museums?

J.D. Artists like Warhol and Bob Rauschenberg also received early museum support from Europe, and some thing similar happens when European artists are welcomed more warmly in America. Sometimes the perspective people have a continent away allows them to see the art more sharply. I do think there’s a broader definition of what art can be among European audiences, and many European curators can simultaneously appreciate Keith’s art on the street and the Pop Shop and his really great paintings and drawings. American curators tend to be more academic. Again, when they see kids around wearing Haring T-shirts, it prevents them from recognizing the quality of the other work. So, in a way, we are still fighting that battle with Keith, and working with the Haring Estate, to democratize and expand art.

G.M. Was Haring’s decision to work in the subway a conscious strategy to connect with the culture of advertising and mass media?

J.D. Keith definitely had a dialogue with advertising, creating images that communicated strongly to people. Keith’s images were essentially about drawing. They were done with chalk. Drawn chalk – it was shocking to see something from the hand in a context where everything else was printed or photographed. Again, the hand is so important to Keith. You see it in the paintings, too, the drips that are part of the heritage of abstract expressionism, Pollock, and de Kooning.

G.M. Could we say that he embraced the same strategies of communication as the graffiti artists?

J.D. Keith had a strong rapport with graffiti artists. He was part of that circle, friendly with a lot of the key people, and he worked in collaboration with artists like LA II (Angel Ortiz). But he was fundamentally different from the wild style artists. People saw Keith working in the subway. He had Tseng Kwong Chi following him around, photographing him doing almost all of those drawings, so there was an element of performance in it that was very important. The kids who painted on the trains did it secretly, climbing into the yards after dark when no one was there. Part of Keith’s intention was that the work was supposed to be done in public.

G.M. Haring is still considered by some critics a ‘light’ artist, but his journals reveal a complex artistic back ground and sensibility.

J.D. Keith had a very good art education, starting with his visits to the Carnegie in Pittsburgh and his attendance at New York’s School of Visual Arts. He had a background in general art history, the New York School, and then, in particular from studying with Joseph Kosuth, in conceptual art and other radical ideas. Even though there’s an element of naiveté in the simplicity of the works, he is not naive at all. Keith mentions the Pierre Alechinsky exhibition at the Carnegie as an influence. He saw it when he was very young. You can see the connection, the obvious interest in all-over painting that he gets from mid-century artists like Alechinsky and Pollock, and there is certainly a consciousness of such early twentieth-century masters as Picasso and Leger.

In the same way, Keith reveals a lot of knowledge about music – jazz and soul, its rhythm and structure-but he was central to the whole development of garage music and house music. He is one of the primary links between hip hop from the South Bronx, gay dance club culture, the conceptual art culture of the Lower East Side, and street art culture. He put all these things together. In his lifestyle and his circle, and, obviously, in his art.

This essay is published in The Keith Haring Show

(Milan, Italy: Skira), 2005. P. 81 – 85.

Catalog edited by Gianni Mercurio, Demetrio Paparoni

Exhibition curated by Gianni Mercurio, Julia Gruen.

Fondazione Triennale di Milano

September 27, 2005 – January 29, 2006

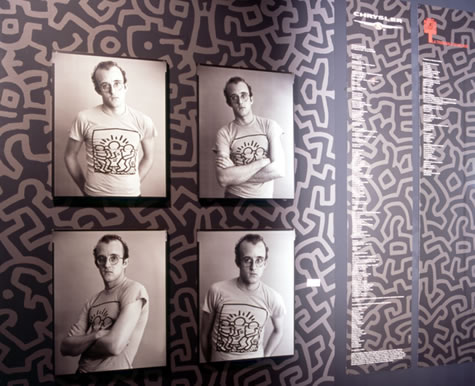

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano

Installation View – La Triennale di Milano