Keith Haring is not unknown to artists in the Czech Republic. His characteristic and easily recognizable style had already spread all over the world, including to the countries behind the Iron Curtain of the time, more than 20 years ago. Haring’s drawings, paintings and prints became symbols of the new artistic energy of the 1980s. Nonetheless it is only now, more than 17 years after his death, that his first exhibition is taking place here.

Keith Haring is not unknown to artists in the Czech Republic. His characteristic and easily recognizable style had already spread all over the world, including to the countries behind the Iron Curtain of the time, more than 20 years ago. Haring’s drawings, paintings and prints became symbols of the new artistic energy of the 1980s. Nonetheless it is only now, more than 17 years after his death, that his first exhibition is taking place here.

Haring’s work did not fail to leave a trace on the Czech creative art culture of the 1980s and 1990s. There are, however, a number of circumstances here which limit this influence to only certain aspects of Keith Haring’s work. His work is connected with the development of the phenomenon of street art. In American big cities, and above all in New York, a strong group of artists came together at the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s who created their work outside of the established artistic institutions and hierarchy. This was by no means only a matter of the graffiti artists. The founders of numerous independent magazines, protagonists of the No Wave film movement and last, but by no means least, also pioneers of the musical styles of new wave, hip hop, rap and sampling belonged to the same generation. All of them displayed an immediacy that was unencumbered by tradition. They were not connected to elite conceptual art or art rock. Their work was characterized by colourfulness, clarity and ironic humour. Thanks to them, anonymous street art, fashion, popular culture and avant-garde art were combined to a hitherto unseen extent.

A similarly strong street art movement did not exist in Czechoslovakia, nor could it exist. If art in a public space was intended to survive for longer than a few hours, it had to have an official blessing and to be in an artistically completely neutral form. Graffiti in the United States was indeed also illegal and its authors pursued, but in another way than in totalitarian countries. Moreover, at the beginning of the 1980s graffiti in the USA lost its unambiguous classification as vandalism and began to be perceived as a peculiar manifestation of visual artistic culture. Graffiti finally became fashionable and its authors – at least for a time – celebrities.

Graffiti did not exist in Czechoslovakia before 1989. Occasionally a sprayed graffito appeared expressing allegiance to a football club, or admiration for a music group. There was, however, a complete lack of graffiti as a means of conscious, creative self-expression, as produced by Keith Haring, who was one of the leading proponents of this type of work at the time1. Even though independent cultural activities began to take place in Czechoslovakia in the 1980s, the artists mostly had to operate in secrecy and fight with state offices, which regarded free manifestations as ideologically suspicious. Although the space for Czech New Wave music was limited to only a few music clubs, in 1983 it was even more curtailed2. A similar situation reigned in theatre and film and was perhaps most restrictive in the plastic arts. An apparently natural thing – to exhibit what I want, where I want and how I want – was not at all a matter of course in the Czechoslovakia of that time.

In the beginning, Keith Haring and his friends did not have an open door to galleries and museums – even in the United States. In 1980, the 22-year-old Keith Haring took part in the now legendary Times Square Show. The artists exhibited their works in an abandoned building located, in one of the then-crumbling centers of New York. Their works expressed their close contact with urban culture. Alternative exhibition spaces were at that time the only means of staging large-scale and independent events of this type. The European artistic group Normal also exhibited at the Times Square Show. This may have been the closest that Keith Haring came to meeting Czech artists at any exhibition.

Normal was actually founded by Milan Kunc, who attracted both Peter Angermann and Jan Knap into the group. They, however, had already left Czechoslovakia in 1969 and could not maintain contact with the domestic artistic scene. Even if Kunc and Knap ranked amongst the European painters who had revived painting after years of conceptualism, their appearance at the Times Square Show differed from that of the American artists. Their pictures did have a similar lightness and energy, but they adhered far more closely to the tradition of European painting and were rather repelled by American street culture.

The independent atmosphere of the Times Square Show in some ways resembled the Confrontation exhibitions of young Czech artists in the 1980s. They belonged to the same generation as Keith Haring and analogously presented a kind of new wave of Czech Art. They did not want to wait for an official opportunity to exhibit, and began to show their works semi-legally: in flats, in urban courtyards or in village farmsteads3. These exhibitions tied in with the ethos of the cultural underground and at the same time they also carried within them the new energy of post-modern art. Painters returned to expressive and rapid paintings, worked with clear colourfulness and with a bold contoured line. They were attracted to working with the language of simple artistic symbols. We would, however, look in vain here for direct inspiration from Keith Haring, even if these artists well knew about his work. In 1982, Haring took part in the celebrated Documenta 7 exhibition in Kassel, whose echo and catalogue also arrived in Bohemia. An article and reproductions of Haring’s works appeared in the magazine Flash Art in 1983. It was in relative terms the most accessible of the international journals about contemporary art in our country4. The painter Vladimír Skrepl remembers coming across Haring’s work in the catalogue from the New York Now exhibition, which took place in the Kestner Gesellschaft in Hannover at the turn of 1982 and 1983. Jirí David also places his first encounter with Keith Haring reproductions to roughly the same period.

Both artists at that time regarded Haring’s displays as interesting and refreshing. At the same time, however, they proferred the opinion that German wild painting and the Italian Trans-Avant-Garde played a more important role for the local scene. “Haring was different from art in Europe,” Skrepl already appreciated at that time. “However,reproductions of his work brought us at least a little closer to art from the otherwise inaccessible New York.” At that time, Czech artists were painters in the true sense of the word. They were mainly interested in new possibilities of the language of the hanging picture or later in its overlap with spatial installation. The world of graffiti or of the individual subcultures of the American big cities was remote to them.

It is of course similarly limiting to perceive Keith Haring solely from the perspective of street graffiti. Haring differed greatly from most American graffiti artists. He had an artistic education behind him and he was interested in the history of art and in contemporary artistic currents. He was not only influenced by the art of Egypt and the Mayan Empire, but was inspired by the European classics of modern art – Matisse, Léger and Alechinsky. His works in public spaces only made up a fraction of his artistic production. From the beginning of his artistic career, Keith Haring was simultaneously interested in social topics and politics. However, he never slipped into left-wing agitation, whether addressing the danger of atomic energy or criticizing conservative American politics. The activist aspect of his work intensified even more upon his learning of his infection with HIV. His work became one of the symbols of the battle against this disease and it is also thanks to him that people began to speak more openly about this illness and protecting against it.

In Czechoslovakia, nobody could openly criticize the societal or even the political situation. At the same time, every independent cultural initiative had an involuntary politicizing charge. This was mostly very general and only perceptible to a public living in a totalitarian society. Most of the things that Haring criticized in his work were not nearly as acute in our country. The content of Haring’s work could therefore only have a limited impact here. As a result of the impossibility of free travel, the AIDS epidemic did not reach us until the second half of the 1980s, and its impact was much less severe (credit for this is also due to the information campaign which Haring and his friends helped to start). Drugs were also only a marginal problem before 1989 in Czechoslovakia. Last but not least, it is necessary to mention the still present taboo of homosexuality in Czech culture today. Czech artists living in the last years of the communist regime were mainly attracted by the liberal-mindedness and form of Haring’s art, without exactly identifying with his individual themes.

*

In 1986, Keith Haring created a 300 meter long painting on the western side of the Berlin Wall. It underlined the absurdity of the city that had been cut in half, and expressed hope for the unification of the politically divided world. In time, the painting was covered by the works of other artists, and after 1989 and the resulting destruction of the wall, Haring’s mural completely disappeared. What was the fate of Haring’s works and his relationship to our art after the end of the Cold War? Was his influence covered and destroyed by new historic events in a similar way as his mural had been on the Berlin Wall?

The fall of Communism meant the renewal of the dialogue with the world, for Czech culture and Czech painters were able to get acquainted with Haring’s work with their own eyes on their journeys abroad. Some of them were surprised by the extent that Haring’s motifs appeared on fashionable clothing or on objects for daily use. The printed t-shirts or even Haring’s own New York outlet Pop Shop could create a sacrilegious impression on an artist from the east. The environment to which they were accustomed anxiously distinguished “high” art and “salable” commercialism. It was difficult to understand that this aspect of Haring’s work was not dictated by a desire for profit. In reality, the decorated objects became a similar public medium for Haring’s art as had his earlier subway drawings. Paintings in galleries, murals on city walls or images on mugs were equivalent channels of distribution for the artist who had been influenced by Pop art and street culture. And for Haring, the establishment of his own shop meant, amongst other things, control over imitations of his own work in the sphere of design. Stanislav Diviš commented with hyperbole: “Everyone, whose work becomes part of pop culture must appreciate this fact. It is one of the greatest privileges a painter can receive, if his work is also registered by the world of design.”

We can consider a series of sculptures entitled Babies, by David Cerný from the years 1995-2001, as an individual homage of Czech Art to Keith Haring. The works are now placed on the Zizkov television transmitter. The giant toddlers have been released into an urban space and function here like three-dimensional graffiti. They also emit a mysterious energy as did Keith Haring’s radiant babies. The first generation of Czech graffiti writers also formed a relationship with Keith Haring. One of them, Vladimir 518, perceives his work as an example of crossing the narrowly defined boundaries of grafitti: “The work of Keith Haring or J. M. Basquiat are points which connect the world of graffiti with the world of the wider conception of art. I love the natural way Haring transferred the street art atmosphere to the gallery environment. I also cannot say that I would regard his manner of working as being too intellectual for grafitti. I was rather struck by its healthy simplicity and directness.” Keith Haring managed to transfer these characteristics into several disciplines at once. Therefore, his works today do not only appeal to painters and grafitti writers, but also to graphic designers, political activists and of course all those who identify with the results of their work.

Tomáš Pospiszyl

Footnotes

- Classic graffiti arrived in Czechoslovakia as a cultural import after 1989. The first work by local authors came into being after 1991 and is credited to individuals such as Mascee & Chise or Rake, so with regard to New York it was delayed by a whole quarter century.

- The repression against music clubs and the prohibition of officially working of individual groups was unleashed by an article New wave with an Old Content, which came out in March 1983 in number 12 of the weekly publication Tribuna.

- The first Confrontation was put on in June 1984 and six of them in total took place by the end of the decade. Their chief organizers were Ji_í David and Stanislav Divi_.

- Texts about Keith Haring could not appear in Czech until after 1989. Attention was originally mainly devoted to him by the unofficial magazine Vokno “for a second and other culture”. An extensive interview with Keith Haring from the magazine Wiener was printed in number 17 and in number 19 there was a text by Keith Haring himself from the magazine Flash Art and an interview with Francesca Alinovi. See Vokno nr.17, 1990, pages 52-56, and Vokno nr. 19, 1990, pages 44-49.

This essay accompanied the exhibition:

Keith Haring Graphics (selected images below)

Egon Schiele Centrum

Cesky Krumlov, Czech Republic

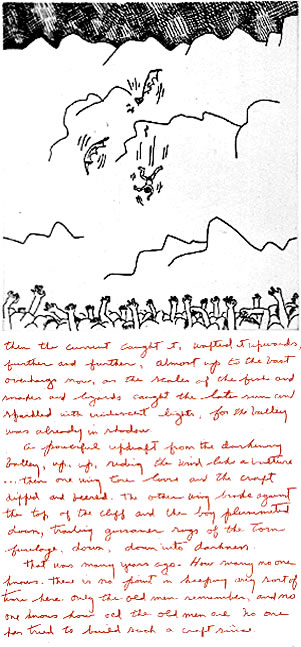

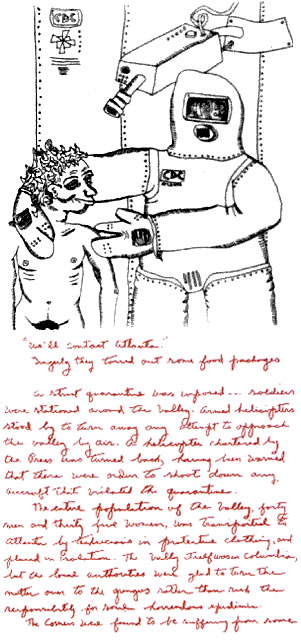

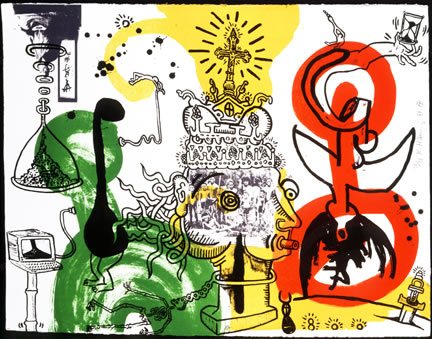

Apocalypse, 1988, Silkscreen | 38 x 38 inches | 96.5 x 96.5 cm

Text: Willliam S. Burroughs

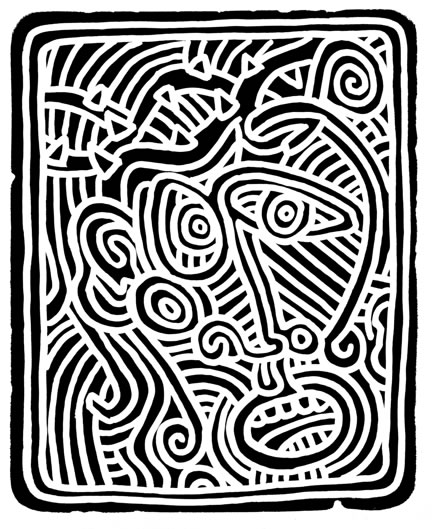

The Valley, 1989, Etching | 10 x 9 inches | 25.4 x 22.8 cm

Etching | 10 x 9 inches | 25.4 x 22.8 cm

Untitled, 1989, Etching | 12 7/8 x 11 1/2 inches | 32 x 29 cm

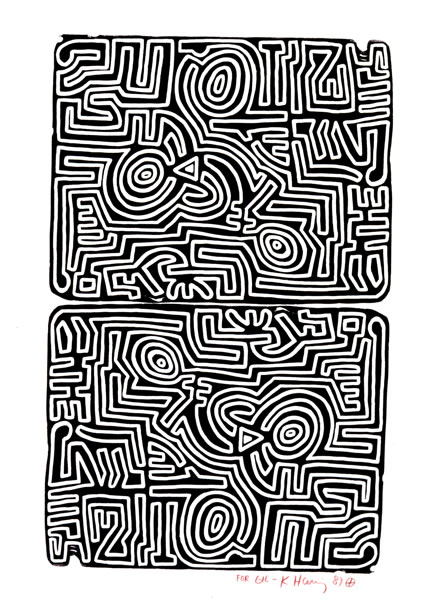

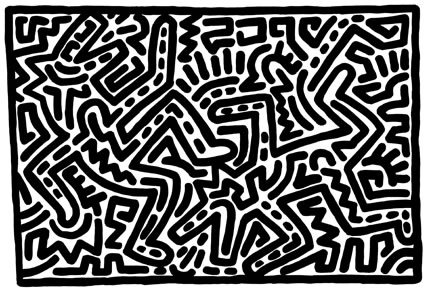

Labyrinth, 1989, Lithograph | 29 1/2 x 41 1/2 inches | 75 x 105.5 cm

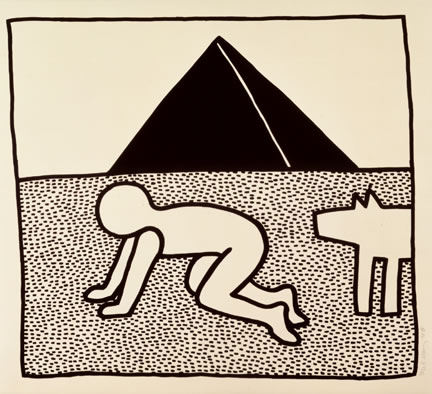

Untitled, 1982, Lithograph | 24 x 36 inches | 61 x 91 cm

Untitled, 1982, Lithograph | 24 x 36 inches | 61 x 91 cm

Lithograph | 23 x 29 3/4 inches | 58.5 x 75.5 cm

Chocolate Buddha, 1989, Lithograph | 30 x 27 3/4 inches | 56 x 70.5 cm

Stones, 1989, Lithograph, 30 x 22 1/4 inches | 76 x 56.5 cm

The Blueprint Drawings, 1990, Silkscreen | 42 1/2 x 46 1/2 inches | 108 x 118 cm