The weird boxed and numbered [New York] space we live in is already fantasy. Artists have only to start with what’s there and give it a few fillips fo the truly fantastic to emerge.

– John Ashberry, Reported Sightings

Keith’s death is incomprehensible. I refuse to believe that the next time I ring the bell to his Broadway studio, just south of Great Jones Street, he won’t be there – Great Jones Street where I ignored bad weather in February 1985 because I knew Keith was at one end of the block, Jean-Michel at the other, and Keith’s friend Kenny Scharf in between.1 Or summer 1984, when Houston was virtually Haring Boulevard, what with his hip-hop mural at the corner of Avenue D, his studio at Broadway, and various tags and images all in between. In 1987 and 1988 as well, I’d ring Keith’s bell, and take the elevator to his neat and gleaming studio, stand in wonder before new paintings in progress, and suddenly there he was, cool, lean, and humorous, eyebrows moving like the “action lines” that animate his figures, lips pursed for the punch line.

Artforum title page, May, 1990, Untitled #8, 1988

Acrylic on Canvas

60 x 60 inches

When Bird died, and James Dean too, in 1955, the world refused to accept their absence. That same defiance, an aura written in chalk and tears, has sprung up all over New York since Haring died, 16 February 1990, at the age of 31. Graffiti in his honor appear on walls and sidewalks. Some of them allude to the fact that AIDS, slowly but inexorably, is destroying members of one of the most open and brilliant generations in the history of American art.2

Keith was as self-taught as the visionaries. His success in moving between popular art and arte erudita (I refuse to call it mainstream) was greeted with confusion and contradiction. The fact that he fluently and powerfully combined the voice of the street and the voice of the gallery system was threatening to those dependent upon a clear sense of ladder, a reassuring braille of social hierarchy. And so “they” bracketed his work as “subway.” They pretended shock when he turned a portion of his art into an industry, as if artists had no right to control their own destinies in the ongoing combat with commodification.

Some critics genuinely loved his work and understood what he was trying to say. Others, not. But the people: no problem. He spoke to them and they spoke back to him. Mutually they deepened imagery and meaning in America. On New York’s Lower East Side in 1986, Latinos leaned out of tenement windows to cheer him on while he painted a mural of allusion, attacking crack,extolling life.3 Because they knew. Knew that he had invented an extraordinary pictorial language that spoke to the city, spoke to the ’80s, spoke to the whole damn world. Inventively he drew the terrors and the pleasures of our times – the threat of nuclear annihilation, religious bigotry, the fusion of cultures in the dance, the brotherhood of the boom box -all by cartoonlike ellipsis. He graced Grace Jones with body paint. He painted the Berlin Wall.4 He chanted the paranoia out of our system, chalk-tracing parody and paraphrase. All this with a supreme self-confidence. I never knew a person who was more certain of his place in world history and who was less conceited about it, taking no credit for the powers of his hand.

Untitled, 1981, Marker Ink on Fiberglass 40 x 28 inches

The story of Keith’s art bears witness to a rising multi-traditional state of affairs where Europe-derived art history and criticism must hack it, democratically, in terms of competing streams of influence from Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. Adieu Euro-American insularity, hello world beat. Keith leads us toward this richer amplitude. His work, I think, helped “deterritorialize” art and criticism, pushing as far into the vernacular, as far into academic idioms, and as far into commerce as he wished, all at once. He showed us that the art and dance of the blacks and Latinos, if woven intothe “art of New York,” could establish that city as a world creative center beyond belief, drawing on its incredibly Alexandrian mix of Christian and Jew and Rasta and Olocha and Candombleiro and Abakua. As one of the deepest portions of this achievement, Haring poetically translated electric boogie and the break dance into his special idiom. Experimenting with these African-American choreographies of the ’80s, he established a down-to-earth humanism, idealizing human beings in the richness of their moves and affirmations.

The Informing Spirits

Timothy Leary. Andy Warhol. Allen Ginsberg. Grace Jones. Jean-Michel Basquiat. William Burroughs. These, Keith told me one evening, were the persons in his pantheon.5 And you could see that he meant it when you visited his studio – a sticker on the door with a saying by Leary, a poster of Jones, works by Basquiat, Warhol soup cans. At variance with “the mainstream,” these people taught him possibility and freedom.

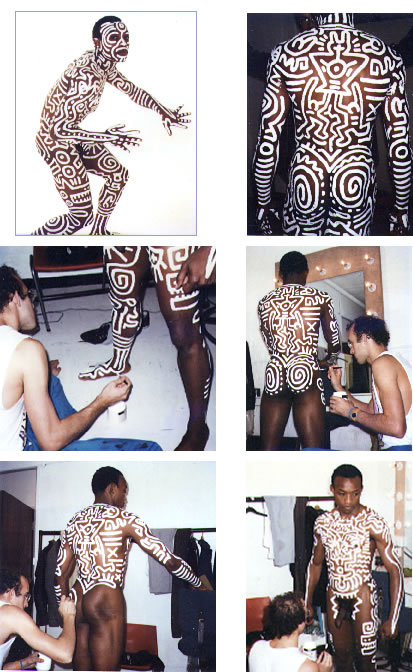

Untitled (body painting), 1983, Acrylic

Keith was a Jesus freak at the beginning of his adolescence, in the early ’70s. He was hungry for religious passion, which he later rediscovered in the structures of black dance. Finding out, in the middle of the ‘7Os, about marijuana and Leary opened him up. Drugs, he told me, “immediately made me understand connections between things. They taught me how to break the sky up into pieces, how color attaches itself to the eye.”6 This move toward freedom of visual expression was accompanied by self-exorcisms of certain demons of the modern age. Consider Haring’s drawings of the early ’80s. Figures with crucifixes stab their neighbors in the back.7 The cross appears on television while a person calmly sits bound to a chair and is played with by a sadist.8 Haring was drawing what Latinos call cristazos, where people are literally hit over the head with Jesus, where the security of one system of religion is built on the insecurity of others. The critique was rich and prescient: the cross become a television set broadcasting dollar signs predicted, in an odd way, the fall of the televangelists.9

The message of Leary, however inappropriate for some, in Haring’s case fit well. Leary taught him, in effect, to find spirit and intensity in popular forms, beyond the control of the major organized world religions. “Just say know,” Leary said. This was the saying that Haring pasted on his studio door.

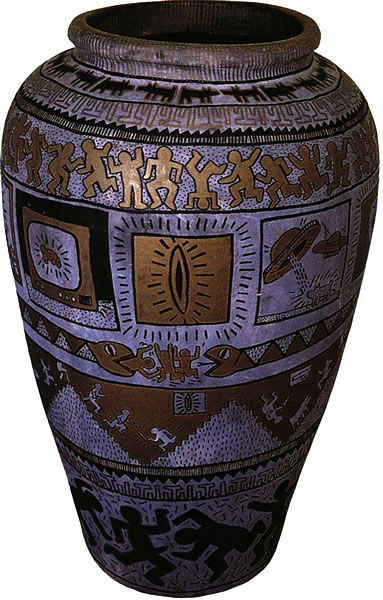

Keith’s cristazos occurred simultaneously with other exorcisms.10 Certain drawings showed television screens filled with the image of an atomic explosion. Counter-language to paranoia. It was Haring saying, in effect, put your worst fears in a drawing, play-back your nightmare, and get on with it. And he was a master of high-tech imagery, but never to the point where gadgets seemed more interesting than people. His robots parodied the impossiblecuteness of Star Wars-type creatures. His sci-fi paraphrasing and humor protected us from feeling obsolete. Haring drew telephones and spaceships on canopic urns, mixing antiquity and technology. He painted the pyramids of Egypt zapped by alien spaceships. Granting equal potency to the languages of then and the languages of now, he was role-switching his way to a grand reconciliation, much needed in the ’90s, where virtually everywhere traditional folk trek to the high-tech cities, looking for jobs. Haring also drew spaceships zapping male members – “the power in their rays went into their dicks.”11 And there were follow-up drawings miming the sequential logic of the comic strip, showing men spreading, sexually or otherwise, this strange electricity.

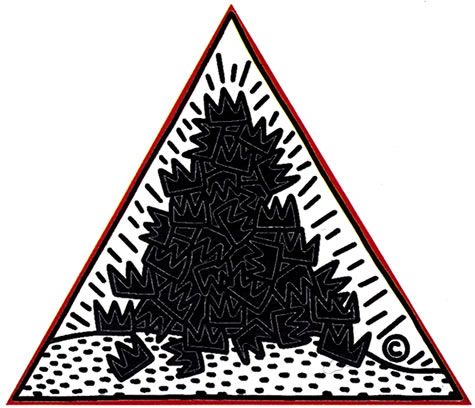

A Pile of Crowns for Michel Basquiat, 1988

Acrylic on Canvas, 108 x 120 inches

Haring had studied semiotics, had studied gesture and image, and how they interact, as instruments of signification. And he served that knowledge well. But friendship with Warhol was much more to the point. From Andy, Haring learned not only the power of the sign in art but how to be that sign. Warhol taught him the power of discernibility: “Andy,” Haring told me in 1988, taught him “to bring back signs, at a time when they were really needed.”12 Warhol’s influence on Haring was conceptual, rarely visually direct. One exception is Marilyn Monroe, 1981, painted as homage, but precious differences announce independence from the master: the film star is updated with New Wave makeup and the background seethes with ’80s graffitero tagging.13 That work and Portrait of Andy, 1984, were Haring’s way of rendering respect for the “forerunner of the attitude about making art in a more public way and dealing with art as part of the real world.”.14 Haring depicts Warhol more or less in color-negative, purple for flesh, yellow for lips, but leaves the famous shock of bone-white hair coloristically intact. Warhol’s eyes are spirals; he appears against a field of plus signs; his garment is dotted – all intuitions of the translation of life and art into semiotic process.

Allen Ginsberg taught Haring another kind of bravery. Ginsberg, the story goes, during a reading, when queried about the meaning of “nakedness” in one of his poems, calmly took off his clothes. Keith, not to be outdone, posed naked, dressed only in Afro-Atlanticizing signs, one evening in the summer of 1987, in the middle of Times Square. Many of the lines, painted in black on a ghostly white ground, emphasized the major body joints, like the Afro-Cuban (more technically, Ejagham-Cuban) ireme(?) whose imagery Haring knew from reading. “I was standing in an overcoat, before the camera clicked, looking for cops.”15 With this prank he realized an ultimate graffitero dream: he tagged Times Square with his naked body.

The semiotic dimension to the paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat reinforced what Haring learned fromknowing Warhol and reading Umberto Eco. The young black painter broke philosophy and communication down into percussion-driven fragments. When Basquiat once wrote on a wall in Manhattan, dressed in an overcoat, one foot crossed behind the other, as if he were executing a mambo turn in Harlem16

THE WHOLE LIVERY LINE

BOW LIKE THIS

WITH THE BIG MONEY ALL

CRUSHED INTO THESE FEET

– he was dealing with poetry and social critique. Haring resonated to the lesson.

Capoeiro Dancers, 1987

Polyurethane Paint on Aluminum

28.5 x 28 x 25 inches

Basquiat gave Haring compositions, including a work that opposed the legend BABEL with NEPTUNE, colliding languages and oceans, and recalling Haring’s own early works of 1979 that fused discordant headlines. And Haring’s admiration for Basquiat left a trail of occasional paintings that recall the spirit of the doomed black luminary’s work. He was aware of how competitive Basquiat was. We all were. Was he superior to X, was he better than Y or the famous Z was what he wanted to know. Basquiat saw himself in graffitero terms, as the king of the young painters. The word King, with its concomitant of sovereign composure, Cool or Kool, appeared with great frequency in New York City graffiti of the ’70s. Haring saturates A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1988, with these understandings. He takes the signs of coronation seriously and transmutes them into an epitaph. The crowns are built up, like a mound of stones upon a sepulcher, as if honoring every painting Basquiat ever signed with this seal of assertion. Some of the crowns have fallen, however. The artist is gone, unable to tend his reputation. Haring causes the mound to shine with inner spirit, intuiting a lasting contribution to American painting.

Grace Jones, the tall, powerful black performer, fascinated Haring. He did elaborate costumes, graffitized settings, and body-painting for her, sometimes without pay, “because it was more important to do it – no one else I worked with made as much sense,” he told me in November 1986. Grace Jones led him to perhaps the most famous of all black discos of the middle ’80s, the Paradise Garage in SoHo, where Haring invited me to come and photograph him painting her nearly naked body at 4 A.M. one weekend in the fall of 1985. The Paradise Garage (now closed) confirmed Keith’s vision of blacks on the dance floor as an icon of life and continuity. If, as he argued, he owed some of his most expressive dancing outlines to close observation of African-Americans performing there, then Grace Jones was the ultimate body, the theory most made flesh. The late Tseng Kwong Chi, as always photographing the event, told me that he had seen Keith, in preparation for the commission, poring over photographs of Masai men painting white stripes on their naked bodies. Thus came East Africa to SoHo.

Untitled, 1984, Acrylic on Canvas, 94 x 94 inches

The strange and tortured contributions of William Burroughs to literature include the notion of the “cutup.” That aspect of Burrough’s work fed Haring’s early street art: “Burrough’s work with Brion Gysin with the cut-up method became the basis for the whole way that I approached making art then. The idea of their book, The Third Mind, is that when two separate things are cut up and fused together, completely randomly, the thing that is born of that combination is this completely separate thing, a third mind with its own life. . . by relying on so-called chance, they would uncover the essence of things.” So Haring “cut up headlines from the New York Post and put them back together and then put them up on the streets as handbills. That’s how I started work on the streets… I was altering advertisements and making these fake Post headlines that were completely absurd: REAGAN SLAIN BY HERO COP or POPE KILLED FOR FREED HOSTAGE.”17 Haring was “cutting-up” in a double sense, composing from deliberate fragmentation and being antic, having fun, using humor to work conservative values out of his system. All of which carried over directly into his subway art of 1981-84. For by this time Haring had acquired a strong taste for putting out ideas, cathartically or otherwise, in public places. The cut-ups, the fake headlines, had honed his eye. Such that one famous day when he noticed unused black advertisement paper in the subway, he was instantly galvanized.

You get a sense of the humanity to Haring’s politics when reading his subway drawings. Unlike the cold eye cast by Burroughs’ third mind, his eerie juxtapositions work morally. Fascism was a target. So was commodification: the chalked outline of a robot was caused to cop a hot dog from a neighboring advertisement. Actually Haring’s subway drawings themselves were never-never advertisements, not only for himself, in a Mailerian sense, but also, and increasingly as time went on, for the black and Latino artists of hip-hop, their moves and culture. The drawings were a proving ground, a highly public mode of self-instruction, or, to borrow the art historian Judith Wilson’s phrasing, a “self-definition, an announcement of real or wished-for affinities of style or content, a register of ambition.”18

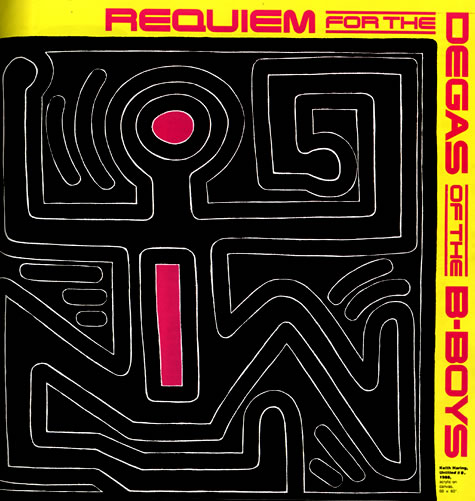

There was no question about what Haring wanted to be one with – America in those years was going through the era of the electric boogie and the break dance. It was one of the century’s richest phases in African-American choreography, as rich, in fact, as the mambo phase of 1949-59 or the lindy period of the ’30s. Haring had the vision to see the importance of what was happening. In his book on jazz dance, Marshall Stearns had lugubriously predicted the death of this vital aspect of Americana. But fortunately the chain of transmission, through James Brown, Michael Jackson, and other artists, was stronger than Stearns had supposed. New dances exploded on the scene, timed to the arrival of hard and driving beat-box reverberations. Haring took it all down and turned it into images: “1983, 1984, it was almost like a dialogue going on, back and forth, and the subways were a way to continue the dialogue and put [out] images which I would get sometimes specifically from dance moves that I saw. . . you know, [persons who would] bend over backwards [to the floor] or somebody going underneath [in the moves called the bridge and the spider], things that I was seeing in dances and literally putting them right into the work – they knew, when they saw it, right away what it was.”19 “They” were the break dancers. And Haring became their iconographer, the Degas of the b-boys.

Untitled, 1982, Vinyl Ink on Vinyl, 72 x 72 inches

He even matched his body to their moves, in the act of painting. Consider Haring, in sneakers, pants, T-shirt, and leather jacket, drawing a dancing valentine in February 1983.20 His sneakered feet coil up with watchspring intensity. Right heel shoots out behind his body, while weight and pressure fall upon the ball of his left foot. The resiliency and springiness to this position carry directly into the drawing. Haring was working from an essentially kneeling position, covering portions of the paper less than 24 inches above the ground. Tseng KwongChi’s photographs show Haring once again kneeling while painting: Or seated on the heels of his sneakers. Or finishing a barking-dog image, itself six inches above the ground, from a body bent so low, so parallel to the earth, he could almost be en route to an African-Brazilian Angola negativa movement.2I Bending, crouching, kneeling, stretching, reaching – and sometimes running from the cops – Degas became the dancer.

Haring’s Electric Boogie Iconography

Kim Levin, writing in the Village Voice of December 20, 1983, saw it first: “electric boogie calligraphy.” Her insight was echoed by Jeffrey Deitch, writing in 1986: “While [Haring] paints, with intense concentration… advanced dance music [meaning hip-hop] permeates the air, sounding from an immense boom-box. He seldom works without music, and not only Haring, but the figures he’s painting seem to rock to the beat. . . . Like a master rapper who can rhyme line after line in a never-ending cadence, Haring keeps unfolding his images with a visual syncopation.”22

Edit deAk and Lisa Liebmann touched upon another element of the electric boogie in his work. Discussing Haring’s New York show of October/November 1982, they note “a current of energy transmitted by and to male creatures ever-readily recharging themselves or one another… the act of recharging appears to be both praxis and erotic principle.”23 Electric boogie derived its name precisely from its exquisitely percussive parody of the animating powers of electricity, which it sited in the human body. Again and again at the Roxy in New York, early-’80s dancers mimed passing electrical charges, one to another. A dancer would begin an electric wave in his right arm, touching another dancer’s arm, which would vibrate with the received energy and then pass it on to as many dancers as could play this game of electronic calling-and-responding.24 Haring’s most amusing dancer of electric boogie, among the subway drawings: a figure so filled with electricity, spouting sparks from head to trunk, that he lights up a light bulb with the current in his own body.

Haring’s fusion of art with electric boogie humanistically countered, in a black-learned way, the posthominid threat built into robots and computers in the age of the “smart machine.” He must, somehow, have intuited Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s argument that violent oscillations – in this case emanating from an intensely electronic world – only “overwhelm an individual so long as he seeks only his own center and is incapable of seeing the circle of which he himself is a part.”25 In the electric boogie realm the circle is the “crew,” the band of friends or comrades who share the currents symbolically.26 Their dance ideology stems ultimately from the ring shouts of the South, the rodas or circles of capoeira, and the hand-clapping circles surrounding rumba dancers. Ultimately they trace back to the rounds of Kongo, in Central Africa.

All culturally appropriate to the fact that from around 1981 onward Haring developed as his own spiritual copyright mark the Kongo sign of the solar round, a quartered circle signifying the cosmos divided into dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight. In Central Africa, initiates stand on this sign to seal a vow with God and the ancestors.27 When I asked Keith about it, he said, “I had to draw a symbol to get the other world’s [protection], a protective copyright mark that was more than legal, that was spiritually protective.”28

Fall 1984: The For N.Y.C. Mural

Electric boogie is a stand-up dance, a mime of robotic or other electrically induced motion. Breaking is performed horizontally, executed close to the ground in spins and turns and acrobatic thrusts. Or even upside-down, like the cognate Kongo/Angola-derived martial art of Brazil, capoeira. Break-pattern moves to the ground can be seen in Kongo (elsewhere in Africa, too) to this day. With the African diaspora, such moves came from Kongo to Cuba, and from there traveled to Latino New York with rumba and mambo. The rumba columbia is full of them.

As to the roots of the electric boogie, Kongo priests of the classical religion show spiritual ecstasy by jerking and popping their shoulder blades. They call this stylized form of jubilation mayembo or zdkama, and it is illustrative of the descent of the spirit.

Cut to Fresno, California, amongst descendants of black migrants from the Old South. It is the early ’70s: three young African-Americans, the Solomon brothers…were to invent electric boogaloo. While attending services at the First Corinthians Baptist Church on Thorn Street in West Fresno… they saw women in the front row “jerking and trembling” with the Spirit. This may not have been a direct inspiration, but the fact remains that several years later they came up with poppin’ and tickin’, rhythmic angulations of the torso and the limbs, executed at a moderate tempo if one is poppin’ or very fast if one is tickin’.29

Toward the end of the ’70s, the South Bronx absorbed the California electric boogaloo and renamed it the electric boogie, “popping hard, hard waves” to hip-hop drum machines. Some of the finest black and Latino masters of the genre worked “found motions” from television cartoons into their emergent corporeal cubism. As the ancient Greek kouroi developed into the Laocoon, so the Kongolese sending waves (fila minika)30 with the shoulder blades developed into a richer, total body oscillation in black New York. And Haring carried the essence of this brilliance into the subways.31

Untitled, 1983, Chalk on Paper, 28.5 x 24.5 inches

In the fall of 1984 Haring emerged at around 90th and the FDR Drive and painted a long frieze, For N.Y.C., on aluminum siding. To this wall of metal (now dismantled), working in red and black, he brought all his breaker/electric boogie expertise. And with his most inventive figurations here he was clearly suggesting that these New York dancers were the image of social truth and spiritual transcendence, perhaps the richest exaltation that secular North America would experience in the ’80s.

Only a careful monograph will release all the brilliantly condensed cultural energies here. The mural began on a panel at right angles to the East River. Here danced two figures, one with feet apart, the other angulating his arms like the conventions of ancient Egyptian bas-relief, a step the b-boys called King Tut. A turn to the left, and now the mural proper was running parallel to FDR Drive.

The full realm of the spirit in the dance unfurls. Breaker head-spinning, body propelled by one hand, legs pretzeled. Kicking and rolling shoulders. Two-partner balancing act. Vertical electric boogie, the elasticity of which, sending waves, has magically lengthened the dancer’s body. Breaker falling on his back, body supported with the palms of the hands and the feet, building the pose called the bridge. Wave dancers passing modified lightning to one another. Breaker in a swipe move, borrowed from gymnasts but played on the ground, not on a pommel horse. Electric boogie locking, hand right -angled to wrist. Electric boogie dancer whose wave has turned him into a snake.

Further lycanthropy: an undulating caterpillar, pun on the endless, transforming waves of the boogie, wearing a mask with square eyes. (Possibly the mask derived from the Dogon of Mali but more probably it was a transformation of a subway-drawing figure with a television set as head.) Swipes. Locking. Wave-dancing, tying up the dancer in loops. Hand-glide with split.

Fantasy takes over: baby fallen back on one hand, executing a move shared by breakers and capoeiristas that the latter call macaco, the Ki-Kongo and Kongo-Brazilian term for monkey. The infant’s other arm becomes a tiny figure with outstretched arms. Tut dancers put fists through their bodies. Barking dogs pass waves.

Actual steps resume: person executing the difficult spin on one hand, serpent wave dancer passing a current to a breaker about to execute the bridge over a Tut stylist.

Technological terror: a robot, dated ’84, snips off a dancer’s arm with his pincers. More crawling infants.

Right-angle turn to the final panel: Haring’s signature three-eyed face bracketed by two King Tut dancers. At the bottom: “for N.Y.C. K. Haring. 1984.” And a final radiant baby.

Throughout the frieze, babies were several times cast large as the biggest figures, and when I asked Haring about this he said, “Babies represent the possibility of the future, the understanding of perfection, how perfect we could be. There is nothing negative about a baby, ever.”32

Further Quintessence: Afro-Brazilian Capoeira and the Paradise Garage Combined, Stella By Afro-Atlantic Starlight, and the Triumph of Yemanjil over Darwin

The Paradise Garage, Keith told me, “was one of the biggest influences on my entire life… especially my spiritual level. Dancing there was more than dancing. It was really dancing in a way to reach another state of mind, to transcend being here and getting communally to another place. It was all black and totally modern, totally lights and disco. Still, something else was happening and everyone, everyone knew it.33

In a sculpture from 1987 Keith abstracted from the pleasures and incitements of the Paradise Garage a single move and combined it with capoeira. A three-figure work in metal includes a character in red who displays the dangerous capoeira kick with the ball of the foot, benção. But he sets it in space where it can be appreciated as a display of strength without doing harm. A figure in yellow hooks his arm around him, and a figure in blue and purple extends his arms toward the capoeirista and validates him with a classical Paradise Garage arm gesture. Haring demonstrated the move when I first saw the sculpture, at the Lippincott foundry in Connecticut, before it was painted and shipped to New York. The SoHo dancers would curve their arms inwardly, touching or not touching fists in pure percussion, as if mystically embracing the partner in the beat of the music. Sometimes they smashed one fist in the other hand. Maximum high-affect contrast. An embrace and a kick. Black SoHo and Brazil.34 Haring was no longer making cut-ups. He was making the new Alexandria comprehend itself.

And he carried all this elegance, all this sophistication, right into the world of arte erudita. Witness his Los Angeles exhibition in 1988, where, with impeccable taste, he dared to mix the purified forms and colors of classic American abstraction with the scintillations of black New York dancing, with “getting communally to another place.” Untitled #8 pulls the pinstripes of Frank Stella into figuration and, what’s more, slips in a right-angle wrist gesture in the manner of bodypopping it á Ia electric boogie.35 With their bodies, four dancers joined at the hands in Untitled #6 outline color squares like fugitives from the work of Josef Albers, liberated, never again to be wallflowers. Untitled #4 seems a further quintessence of Haring’s work, with interlocking breakdance moves executed by two performers. Color is superb: olive figuration, orange and white outlines, background black. Trace of Stella striping.

Finally, Untitled #2 carries the Paradise Garage embracing-fist maneuver to a mystically logical conclusion. The embracing fists of the two dancers fuse, framing a square of orange.36

Again and again in his last years, Haring sought to capture the more spiritually imbued accents of the breaker/capoeira/salsa/Paradise Garage world to activate the idiom of New York gallery art. Paul Ricoeur with a paint brush, if you will, restoring the hermeneutics of a life force mysteriously hidden by its very popularity and blazing ecstasy. As Keith said, “I’d like to think that it’s all been intuitive and that it comes through by some other channels than, you know, learning it, or reading it, but that it’s really just coming through naturally.”37

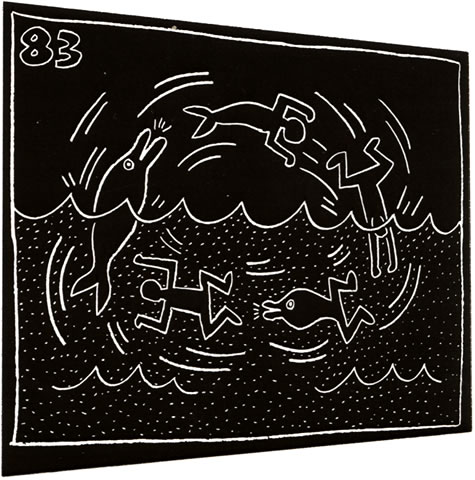

Let me close with a history of a motif. One of Keith’s ideographs somehow captures his art and his aspiration. I refer to the fish-tailed image of Yemanjá, the Yoruba-Brazilian mermaid goddess of the seas. Keith developed this striking image in the subways in 1982: “What happened, really, was that the drawing grew out of an evolution of other images, of the dolphins, of the angels, and sort of combined and turned into this sort of dolphin-mermaid-angel. Then, being in Brazil made that image mean [Yemanjá] by doing it there.”38 Haring spent the winters of the middle ’80s with his friend Kenny Scharf at the latter’s house near IIheus, in Bahia, south of Salvador. The two of them painted the outside of Scharf’s house, which attracted the attention of their black and white neighbors, many of whom were fishermen. “They’d ask us to do something in their houses or on their boats, and we would,” Haring recalled.39 Since hundreds of black and white fishermen in Brazil worship Yemanjá for the fish she brings, and for the protection she offers when they are caught in their barques in a storm, their excited naming of this angelic mermaid “Yemanjá!” was a very natural sequence.

The plentitude of meaning that the fisherfolk of Bahia read into this sign, meanings Haring carried back with him to New York, are matched by the richness of the originating iconographic vortex out of which the sign emerged: a circle of humans turning into dolphins turning into humans turning into dolphins. Haring meant this as a critique of Darwin’s theory of evolution, with its brutalities of hierarchical ranking. “Darwin,” he said, “only goes in one direction.”40 Let this motif rest, then, as the laurel around Keith’s head, where he rejoined himself with the forces of fusion, the forces of dance, the forces of music. So doing, he left, as legacy, the collapse of so-called out and so-called in, so-called high and so-called low, into mysterious ecstasy and reemergence. This roda’s for you, dear Keith.

Robert Farris Thompson is a professor of the history of Africa-American an at Yale University. He is working on a book about African-American New York.

Footnotes

1. I heartily thank Kurt Thometz for guiding me to Haring’s studio in January 1985.

2. Anna Blume, a historian of Latin American art, has kindly documented some of these graffiti in honor of Haring for me.

3. Interview with Haring at his Broadway studio, October 1988.

4. See Time, 3 November 1986, p. 51. As sometimes happened with his work, the commission was as much an act of divination as a work of art: “Haring chose red, yellow and black lines because the colors are found in both countries’ flags and symbolize the ‘coming together of the two sides, East and West, which is the opposite of what the wall is all about.’ “The mural depicts a chain of human figures, running from east to west. Haring lived to see his muralized prayer come true.

5. Interview with Haring, Annie’s Firehouse restaurant, New Haven, II November 1986.

6. Ibid.

7. See Art in Transit: Subway Drawings by Keith Haring, New York: Harmony Books,1984. There is no pagination in this book of photographs by Tseng Kwong Chi, so I have arbitrarily counted each page a “plate,” starting with a Haring-modified Penthouse poster as “1.” See, then, plate “9” and also “27” opposite a 33rd Street subway drawing of dogs.

8. Ibid. plate “10.”

9. Ibid. plate “73.”

10. Haring, 11 November 1986: “These early drawings [were] exorcising things out of my consciousness. ’80-’82 was a clearing-out.”

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. I thank Barry Blinderman, director of the University Galleries, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, for supplying me with a slide of this work.

14. Haring, quoted in David Sheff, “Keith Haring: An Intimate Conversation,” Rolling Stone no. 558, 10 August 1989, p. 64.

15. My interview with Haring and Tseng Kwong Chi, Breezin’ Restaurant, New York, 4 September 1987.

16. The painting of this legend is illustrated in Steven Hager, Art After Midnight: The East Village Scene, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986, on the second page of color plate inserted between pp. 54 and 55. To compare Basquiat’s working stance with black dance, see: Life, 20 December 1954, p. 18: “Harlem… Savoy Ballroom.” For how Basquiat reconsidered this graffito as a painting, in 1987, see: Jean-Michel Basquiat, exhibition catalogue, New York: Vrej Baghoomian, 1989, plate 32, The Whole Livery Line.

17. Haring, quoted in Sheff, p. 63. The period of his work that Haring is talking about is late 1979, according to Hager, who followed his early an closely.

18. Judith Wilson, from a manuscript in progress, The Art of Bob Thompson: A Black Painter of the ’60s. 19. My interview with Haring for the BBC, at his Broadway Studio, 10 November 1988.

20. Hager, Hip-Hop: The Illustrated History of Break Dancing, Rap Music, and Graffiti, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984, p. 66.

21. Art In Transit, plate “20”; cover photograph; plate “2.”

22. Jeffrey Deitch, “The Radioactive Child,” Keith Haring, Amsterdam: Reproductie Asdeling, Stedelijk Museum, 1986, p. 11.

23. Edit deAk and Lisa Liebmann, “Keith Haring,” Artforum XXI no. 5, January 1983,

p. 80. “The character of habitual strength,” which they also note, relates, I think, to the acquired athleticism of Haring’s subway work.

24. See Bonnie Nadell and John Small, Break Dance: Electric Boogie, Egyptian, Moonwalk…DO IT!, Philadelphia: Running Press, 1984, pp. 24~25: “There can be one-, two-, and three-person waves: The flowing motion travels from one person’s outstretched hand to the next dancer’s hand. . . . Sometimes several crew members stand next to each other without touching and ‘pass the energy’ back and forth.”

25. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guallari, Anti.Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p. 21.

26. Nadell and Small, pp. 24-25. 27. See A. Fu-Kiau Kia Bunseki-Lumanisa, N’Kongo Ye Nzá Ji Yakun’zungídila: Nzá Ji-Kongo (The Person in Kongo Civilization and the World That Revolves around Him: Kongo Cosmology), Kinshasa: National Office of Research and Development, 1969. The cover of the book is emblazoned with variants of this ideograph, the sign of the four moments of the sun. And the text is in effect a continuous gloss of this most important sign in Kongo ideographic writing.

28. My interview with Haring, Timothy Dwight College Dining Room, Yale University, New Haven, January 1987.

29. Robert Farris Thompson, “Hip-Hop 101,” Rolling Stone no. 470, 27 March 1986, p. 100.

30. From my interview with Fu-Kiau Bunseki, Yale University, winter 1985.

31. By 1984, however, Haring noticed that the black advertisement paper that he had become famous for drawing on was increasingly being glued on “very lightly, as if planted there” by thieves for immediate removal. (Haring, 11 November 1986.) Which is exactly what happened. Haring would execute his drawings underground and within hours they would vanish from the walls, turning up later for sale. (Parenthetically, this is one of the reasons why Haring decided to found his Pop Shop, so that he could have control over what happened to his work in public.)

32. Keith was generous enough to spend the better portion of the afternoon of 14 August 1985 at a wine bar on West Broadway in SoHo where I unfurled taped-together photographs of For N.Y.C, and he meticulously glossed most of the dancing images. It was a long and glorious interview.

33. Haring, 10 November 1988.

34. At the foundry, Keith led me to another sculpture of two men, again opposing a kick and an embrace. He commented, “Half capoeira, half Paradise Garage.”

35. For a good illustration of right-angled wrist motion in the electric boogie, see Mr. Fresh and the Supreme Rockers, Breakdancing, New York: Avon, 1984, p. 51, upper right hand photograph.

36. Reproduced in Keith Haring: 1988, exhibition catalogue, Van Nuys: Martin Lawrence Limited Editions, 1988, pp. 27, 23, and 19.

37. Haring, 10 November 1988.

38. Ibid. The motif is illustrated in Art ln Transit, plate “33.”

39. Ibid.

40. Haring, II November 1986.